English

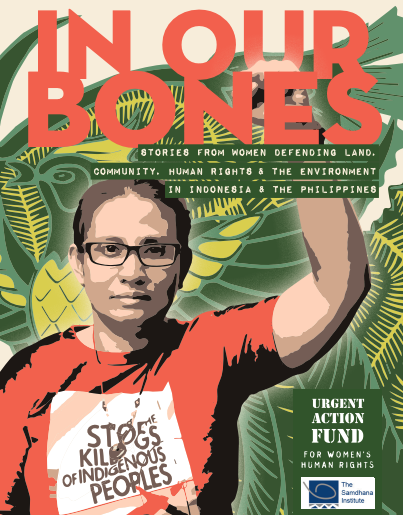

In Our Bones: Stories From Women Defending Land, Community, Human Rights and the Environment in Indonesia and the Philippines (2015)

The report features the stories of nine grassroots women leaders working at the intersection of the environment, human rights, and gender equality.

NEWSLETTER

Our work happens in real time. Sign up to receive our emails and stay up to date.

Urgent Action Fund for Feminist Activism